HRANA- The end of the twelve-day war between Iran and Israel, contrary to public expectations, did not lead to a breaking peace, but rather to a chaotic and unstable situation within the country. During this war and immediately after the declaration of ceasefire, security and military forces of the Islamic Republic began to set up hundreds of inspection checkpoints in cities, roads, border areas, and sensitive urban locations. Official authorities referred to this action as “preventing infiltration of Mossad agents” and “combating spies,” but in reality, these inspection checkpoints turned into clear examples of domestic suppression, gross violations of human rights, and unaccounted for massacres. The project known as “securityization” in Iran after the war, with the true meaning of security at its core, has practically become a tool for controlling society, silencing dissenting voices, and strengthening a climate of fear. This comes while the issue of “real infiltration” has not begun at the borders or on the roads of Hamedan, Zahedan, or Kurdistan, but from within the power structure itself and from the highest levels of decision-making.

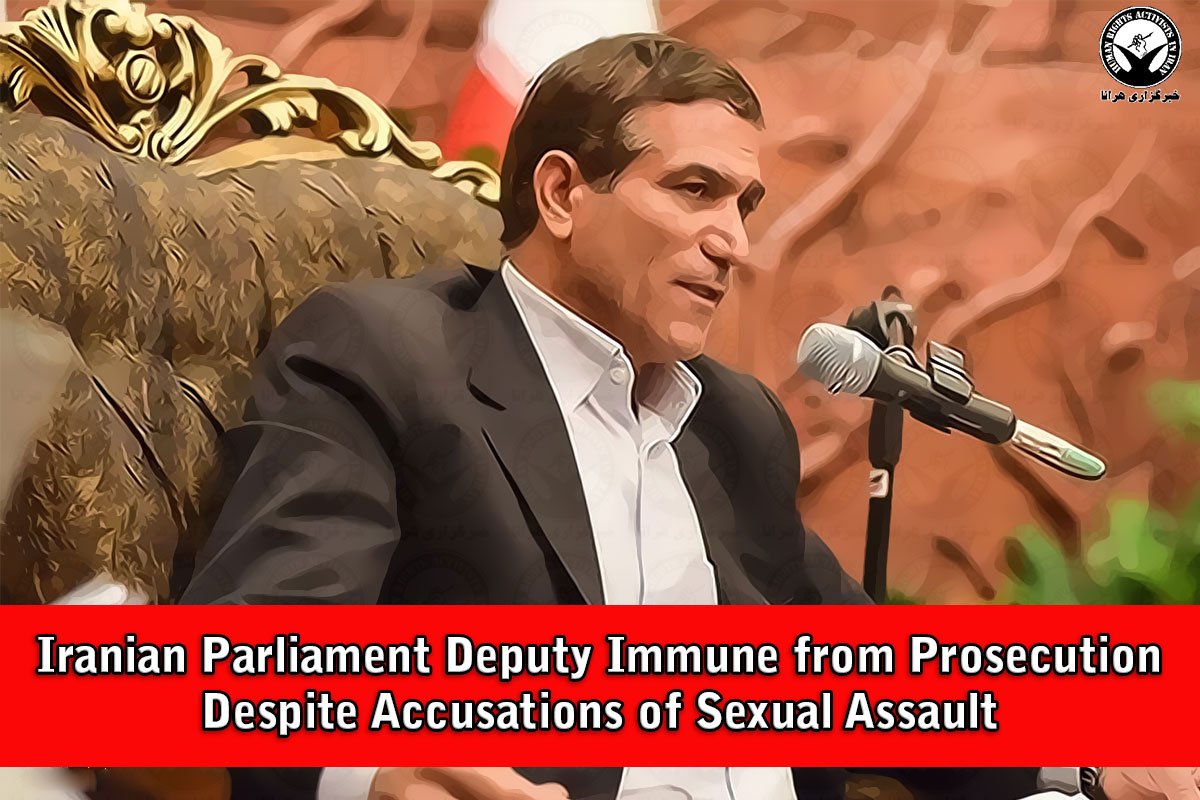

The reality is that the issue of infiltration in the upper echelons of the Islamic Republic has been raised seriously and repeatedly for years. Seyed Mahmoud Alavi, the former Minister of Intelligence of the Islamic Republic, had warned about this issue multiple times. In 2016-2017, at a conference for public prosecutors, military officials, and heads of the judiciary in Mashhad, he stated: “The issue of infiltration today is more serious and fundamental than in the past.” (1) In 1398, in a television program, he mentioned “the projects of foreign intelligence services’ infiltration” and said: “Those who infiltrate usually use the hottest slogans of the government, quickly accuse others, and put themselves behind the sacred fence to remain immune from any suspicion or criticism.” He added: “In no other period, as much as recent years, has the enemy been so close to internal elements. We have discovered spies whose reports have surprised and shocked their superiors.” (2) In

Therefore, if the goal was to combat infiltration, inspection stations should have been established not after the war and in the streets, but years ago, in the heart of the power structure and in the highest levels of government; where the main agents of infiltration, in complete calm, became decision-makers and path-makers. However, in the days after the end of the Iran-Israel war, inspection stations were expanded in Tehran, Kermanshah, Sanandaj, Zahedan, Ilam and other border areas. The forces of the Revolutionary Guards, Basij and the police, with military uniforms and armored vehicles, were stationed in the streets of most cities. Ordinary people, especially at night, were repeatedly subjected to physical searches, mobile phone checks and vehicle inspections. At the same time, arbitrary arrests intensified, and many of those arrested were imprisoned only for having a “suspicious appearance” or “passing without stopping” at inspection stations. It appears that the authorities were seeking to “prevent a wave of post-war protests,” rather than espionage, as security tools were directed not at strategic institutions, but at powerless and marginalized individuals in society.

Casualties in Darkness: A Tale from Hamedan.

One of the most tragic consequences of the securitized atmosphere following the twelve-day war was the “Tarik-Darreh of Hamedan” incident. In July 2025, IRGC patrol forces opened fire on a vehicle at a checkpoint on a side road in the Ganjnameh area of Hamedan. As a result, two young men from Hamedan, Mehdi Abaeii and Alireza Karbasi, were killed on the spot, and a third, Mohammadreza Saberi, was severely wounded.

Security agencies and affiliated media outlets, such as Fars News Agency, quickly released an official account of the incident—without presenting any reliable evidence or witnesses—implicitly labeling the victims as “Mossad agents” and “drone operators.” However, a widespread wave of public skepticism, anger, and a massive turnout at the funeral held in Behesht-e Zahra cemetery in Hamedan soon challenged this official narrative. The victims’ families, through accounts published on Mehrdad Maher’s Instagram page (@mehrdadmaher4), firmly rejected the espionage allegations in detail.

Under pressure from this social outcry, security institutions were forced to retreat. On July 1, 2025, the head of the Judicial Organization of the Armed Forces in Hamedan Province announced that those who had opened fire had been arrested and were under judicial supervision. Yet this retreat was not an act of accountability—it was the result of public pressure. Had the families remained silent, had social media not questioned the state narrative, the truth would never have come to light.

Now that the real story has emerged, and it is clear that two unarmed citizens were shot without warning, a deeper question arises: Will those responsible actually be prosecuted and punished in accordance with the law? Or, like dozens of similar cases, will this be shelved with promises of “investigation,” only to vanish into silence?

The Islamic Republic has repeatedly turned to security-driven narratives to portray victims as the culprits when facing structural violence. But this tactic is nothing new. For decades, the official narrative has not served as a tool of clarity, but as a tool of justification for repression. Wasn’t the same pattern repeated during the Mahsa (Jina) movement? Didn’t the regime, instead of being accountable, accuse Mahsa Amini and her family? Didn’t the same broken narrative resurface in the deaths of Sarina Esmailzadeh, Nika Shakarami, and dozens of other young people across the country?

The killings of Mahsa, Sarina, and Nika are only part of a broader repression. Names like Milad Zareh, Mohsen Gheysari, Hananeh Kia, Erfan Rezaei, Mohammad-Hossein Morvati, and others illustrate the deeper extent of this tragedy—young people full of hope, answered with bullets, simply for shouting: “No to violence, no to lies.”

In the face of this cycle of bloodshed and denial, a final question remains unanswered: If security is achieved only through elimination and death, is it truly security—or merely the shadow of death looming over society? If the Islamic Republic seeks not to address the root causes but to silence dissent, can it still claim any legitimacy for its concept of security?

In a country where the lives of citizens are so exposed and so vulnerable to fabricated narratives, security is no longer a public right—it is an extension of the politics of repression.

Inspection stop or suppression station?

The true function of these checkpoints must be understood through the lived, everyday experiences of citizens. Eyewitness reports clearly show that during these inspections, people’s mobile phones are searched without any judicial warrant. In border regions, residents are often subjected to verbal humiliation, ethnic slurs, and repeated threats. Officers—many of whom are untrained and unaccountable—routinely threaten to detain citizens or impound their vehicles over the slightest protest. In practice, this has turned into a form of “institutionalized lawlessness,” where an armed officer can, with no oversight, decide who is suspicious and who deserves punishment.

The reality is that the widespread and growing presence of armed forces in cities and on roads not only fails to provide a sense of psychological security but directly leads to anxiety, distrust, and fear among the public. For many citizens, passing through a checkpoint is not a reassuring experience but a tense and humiliating ordeal—especially for ethnic and religious minorities and young people, who are targeted solely because of their appearance or style of dress.

What we are witnessing on the streets and roads today is the result of a distorted logic of governance. After its intelligence failure during the twelve-day war, the state, instead of reforming its intelligence structures and being accountable to the public, has turned checkpoints into tools of fear, control, and internal repression. These checkpoints are less a sign of order than a symbol of a ruling power that, rather than rebuilding trust, destroys it at the root with armed force.

The central question in this context is: Does security justify injustice? The prevailing mindset within the Islamic Republic assumes that during times of crisis, fundamental rights can be suspended. But modern Iranian history—and that of many other societies—has shown that when security replaces justice, neither the security lasts, nor the regime retains its legitimacy.

If the government is truly concerned about infiltration and security threats, its first step should be to cleanse the corrupt institutions and ineffective networks within its own security apparatus—not to target environmentalist youth or ordinary travelers on the roads of Kurdistan, Hamedan, and Sistan. A country whose security forces are quicker to open fire on its own citizens than to protect them is clearly rotting from within.

The post-war checkpoints are less a response to an actual threat than a reflection of a legitimacy crisis and political deadlock. What happened in Tarik-Darreh of Hamedan is a serious warning about a dangerous trend: the normalization of violence in the name of “security.” A trend that, instead of ensuring peace and the rule of law, targets the lives of defenseless citizens.

The continuation of this situation will not only further erode public trust but may trigger a new wave of protests, deepen national distrust, and worsen social fragmentation. In such a context, restoring public trust is not just a recommendation—it is a vital necessity for survival. A government that wishes to restore legitimacy must take at least the following minimum steps: offer a clear response to the victims’ families, disclose the identities of the responsible officers, immediately halt illegal searches, and strictly prohibit the arbitrary use of firearms at checkpoints. Otherwise, these checkpoints will become the starting point of an end.

Notes:

1- Alavi: The issue of “infiltration” has become more serious than before.

https://www.tabnak.ir/

News Code: 627347. Date of Publication: 08 Mehr 1395. 29 September 2016

2- https://donya-e-eqtesad.com/

Newspaper Issue Number: 4689 Publication Date: 2019/08/26 News ID: 3564217

3- Former Minister of Information: Mossad has infiltrated Iran, a video of Ali Younesi, former Minister of Information, talking about Mossad’s infiltration in the country.

https://ifilo.net/v/gPjy6sZ

4- What was the story behind the shooting in the Hamedan security patrol? From the Fars News Agency Telegram channel.

5- From the Telegram channel of Mehrdad Maher…

6- Head of the Judicial Organization of Hamedan Armed Forces: Suspects in the shooting case in Tarkhderah have been arrested.

https://irna.ir/xjTXXr

Written by Reza Harisi

Originally published in Khat-e Solh (Peace Mark) monthly magazine on July 23, 2025.