HRANA – Many political and religious prisoners in Iran have endured over twenty years behind bars. To prevent their cases from fading from public memory in the flow of daily news, HRANA has launched a series of reports highlighting their situations. Each installment outlines the prisoner’s legal case, detention conditions, access to rights, and immediate needs.

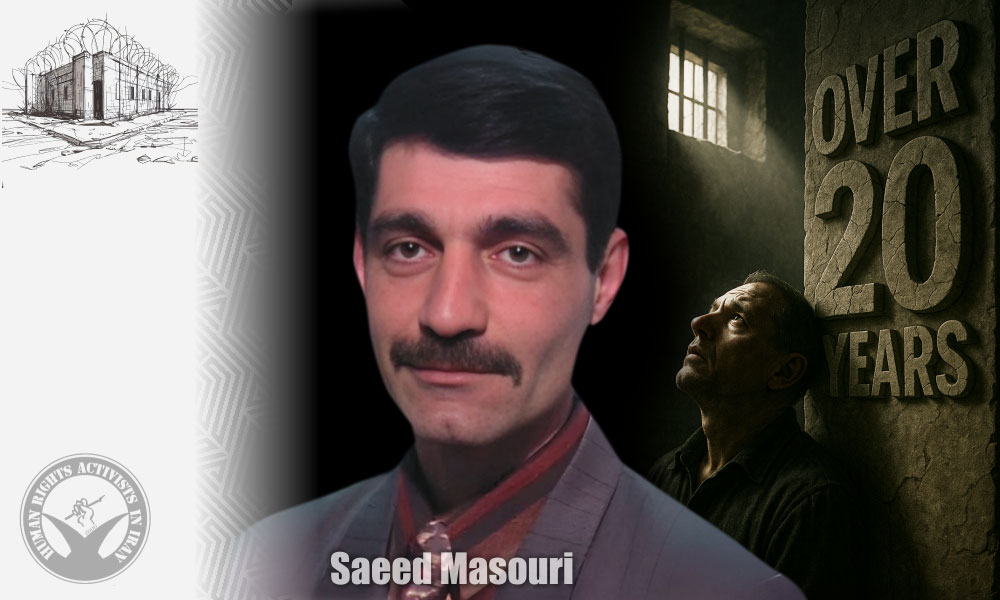

In this installment, HRANA, the news agency of Human Rights Activists in Iran, reviews the current situation of Saeed Masouri after more than two decades in prison.

Profile

• Name: Saeed Masouri

• Year of Arrest: 2000 (1379 in the Iranian calendar)

• Declared Charge: Moharebeh (enmity against God) through membership in the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI)

• Initial Sentence: Death

• Current Sentence: Life imprisonment (commuted by one degree)

• Detention Locations:

◦ 14 months in solitary confinement at the Ahvaz Ministry of Intelligence detention facility

◦ Ward 209 of Evin Prison

◦ Several years in Rajai Shahr Prison (Karaj), including transfers between wards

◦ June 2015: moved to the IRGC-controlled ward of Rajai Shahr

◦ August 2017: forcibly transferred from Ward 12 to Ward 10 of Rajai Shahr

◦ August 2023: after Rajai Shahr’s closure, moved to Ward 8, Hall 10 of Evin Prison, then a month later to Ghezel Hesar Prison

◦ September 2023: transferred from the secure unit (Ward 3) of Ghezel Hesar to Dar al-Quran Hall (Ward 4), designated for drug-related prisoners

◦ August 2025: exiled from Ghezel Hesar to Zahedan Prison; after rejection there, secretly transferred and ultimately returned on August 5, 2025, to solitary confinement in Ghezel Hesar

• Furlough/Access: No furlough reported in recent years; limited access to family and lawyer

• Current Status: Serving life imprisonment despite legal changes that could allow review or sentence reduction

Case History

Dr. Saeed Masouri, born in 1965, lived in Norway for his studies. Upon returning to Iran, he was arrested in Dezful on January 8, 2001, on charges of membership in the PMOI. His family was informed in May 2001.

In 2002, the Revolutionary Court in Tehran sentenced him to death on charges of moharebeh. His sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment. While this prevented execution, it effectively placed him among those serving indefinite sentences, limiting opportunities for judicial review or relief.

Key points in the case:

• Severe security charges: Moharebeh is among the most serious charges in Iran’s political-security cases, carrying broad judicial and punitive consequences.

• Sentence commutation: The initial death sentence and its later reduction to life imprisonment demonstrate both the severity of the charge and the judiciary’s capacity for intervention, but do not necessarily address concerns over fairness of proceedings.

• Continued imprisonment despite legal reforms: Although recent legal changes allow retrial, sentence reductions, or conditional release, Masouri remains imprisoned.

Detention and Transfers

Throughout his imprisonment, Masouri has been repeatedly moved: from solitary confinement in Ahvaz, to Ward 209 of Evin, to Rajai Shahr, and later to Ghezel Hesar and Zahedan. These transfers have often involved violence, including beatings during moves in 2017, 2023, and 2025.

He has staged hunger strikes in protest, including after being beaten and transferred without warning in 2017. Following Zahedan Prison’s refusal to accept him in August 2025, he was held in an unknown location for several days before being returned to Ghezel Hesar.

Observations on Conditions

• Repeated transfers: Frequent relocations disrupt access to family, lawyer, and healthcare.

• Solitary confinement as punishment: He spent 14 months in solitary in Ahvaz, and has repeatedly been returned to solitary in later years, including in 2013, 2017, 2023, and 2025.

• Exposure to violence: Reports document physical and verbal abuse in Ahvaz, Rajai Shahr, Evin, Ghezel Hesar, and during forced transfers.

• Medical neglect: Despite suffering from chronic back pain, eye and dental problems, a broken ankle, urinary bleeding, and needing ultrasound examinations, prison authorities have systematically obstructed his access to specialized care. Denial of medical treatment is considered inhuman treatment and a violation of the right to health and even life.

Access to Family, Lawyer, and Furlough

In recent years, Masouri has been denied furlough. His access to family and his lawyer remains limited, negatively affecting both his mental well-being and his ability to pursue legal remedies.

Potential Legal Avenues (General Recommendations)

1. Retrial (Eda‘e Dadrasi): Based on new evidence or substantive/procedural flaws.

2. Sentence reduction or commutation: If legal grounds exist.

3. Conditional release/suspension: If requirements such as served time, conduct, or health conditions are met.

4. Remedying rights violations in detention: Including access to medical care, freedom from ill-treatment, and regular visitation rights.

5. International documentation and advocacy: In case domestic legal remedies are blocked.

Timeline Summary

• 2000 (1379): Arrest on charges of moharebeh through PMOI membership

• 2002 (1381): Sentenced to death; commuted to life imprisonment

• 2000–2001: 14 months in solitary, Ahvaz Intelligence facility

• 2000s–2010s: Long-term detention in Rajai Shahr Prison

• 2013: Solitary confinement reported; beatings in Rajai Shahr

• 2015: Moved to IRGC ward in Rajai Shahr

• 2017: Beaten and transferred to Ward 10, Rajai Shahr

• 2023: Transferred from Rajai Shahr to Evin, then Ghezel Hesar; solitary confinement and beatings reported

• 2025: Violently exiled to Zahedan Prison; after refusal there, returned to Ghezel Hesar solitary

• Recent years: No furlough, inadequate medical care, restricted access to family/lawyer

• Present: Still serving life sentence

Conclusion

Despite legal reforms enabling retrial, sentence reduction, or release for those convicted of moharebeh, Saeed Masouri remains imprisoned. His case exemplifies the plight of long-term political-security prisoners in Iran. Reviewing such cases is a vital step toward securing their rights and release.

Urgent Needs

• Regular, unrestricted access to lawyer and family

• Independent medical evaluation, especially after reported abuse

• Judicial review of case in light of legal reforms

• Compliance with prison regulations on visits, furloughs, and communication

• Adequate medical treatment

About this Series

This report is part of the “Two Decades Behind Bars” series, which aims to document the cases of long-term prisoners and to highlight the collective responsibility to ensure their visibility and pursue their rights.